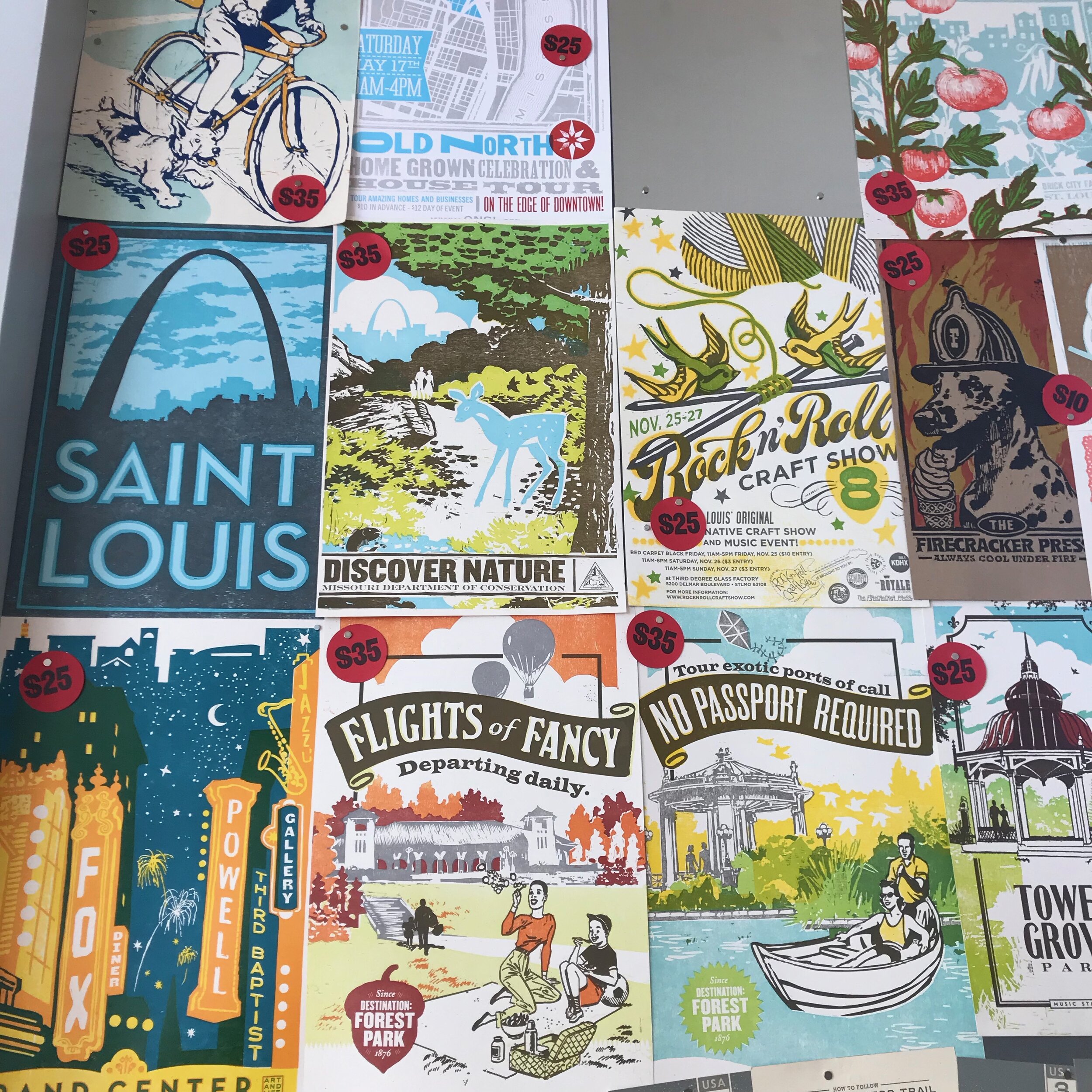

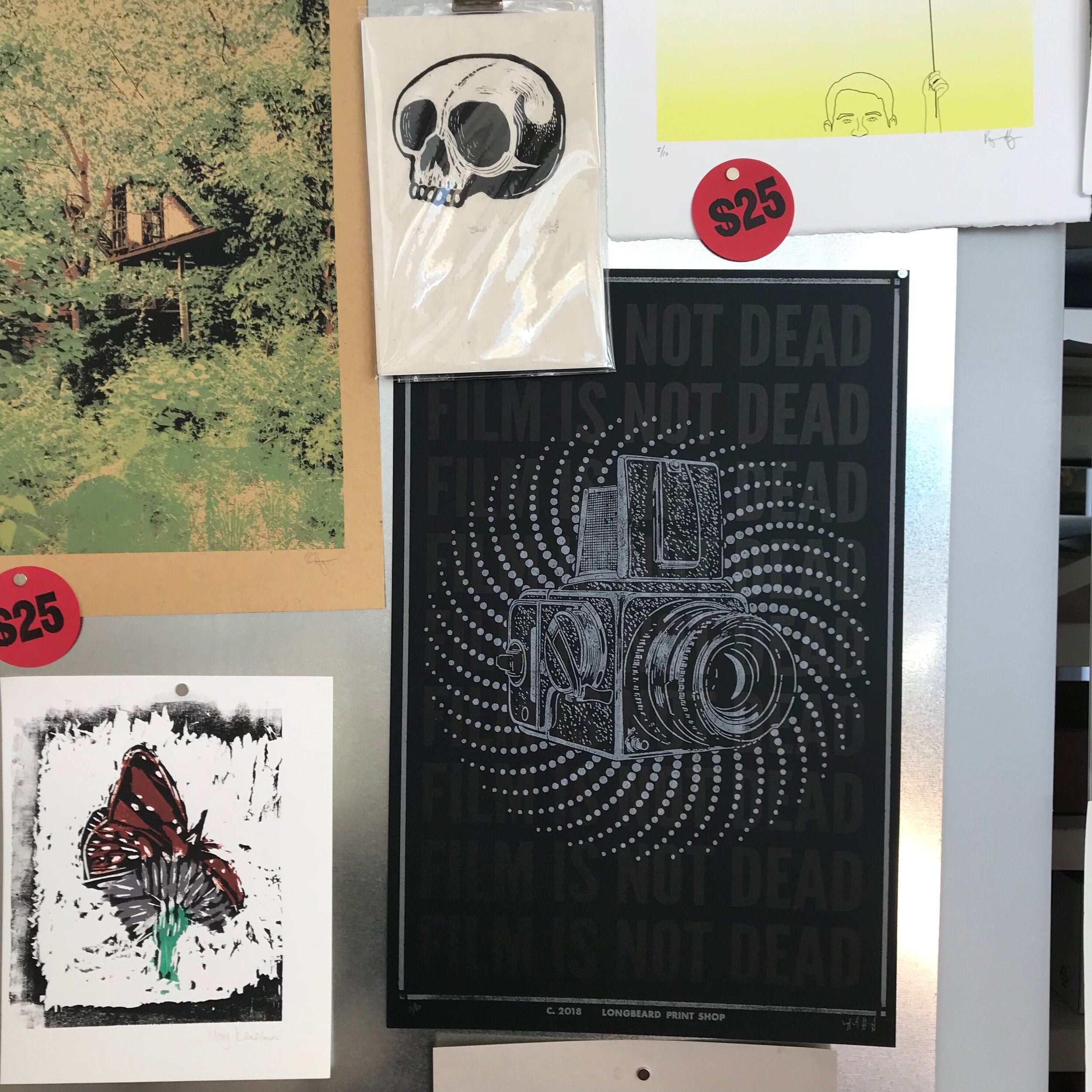

Central Print takes its name from its location at the center of the revitalized historic neighborhood in St. Louis known as Old North. This community letterpress studio functions as a creative space for residents as well as a printing museum. As a resident of Orlando, FL where most structures seem to have been built during or after the Disney-fueled boom of the 1970’s, I was struck by the beautiful historic quality of the architecture of the Old North neighborhood which saw its boom during an expansive growth period in the 1870’s. The homes are primarily red brick, narrow, multi-story structures constructed side-by-side to allow for large families to live within walking distance of local stores and schools. Many of these buildings—-schools, churches, stores and homes— have fallen into disrepair; some literally collapsing in on themselves, overgrown with vines, mature trees sprouting up through the remains of the roof from the ground floor. Structures that were condemned and torn down left behind open grassy lots where some residents have established elaborate gardens and raise livestock. The overall effect is disconcerting at first, an unfamiliar blend of rural and urban landscapes which seem almost post apocalyptic. In the last few years, however, new residents have moved to the Old North neighborhood, renovated these historic homes and businesses, and brought with them a renewed sense of shared purpose around the importance of building community. In my few days there, I could tell from the residents I met that rebuilding Old North is going to be a decades-long, multi-generational collaboration amongst neighbors who are willing to reach out for help when they need it and are not afraid to carve out a new kind of urban life.

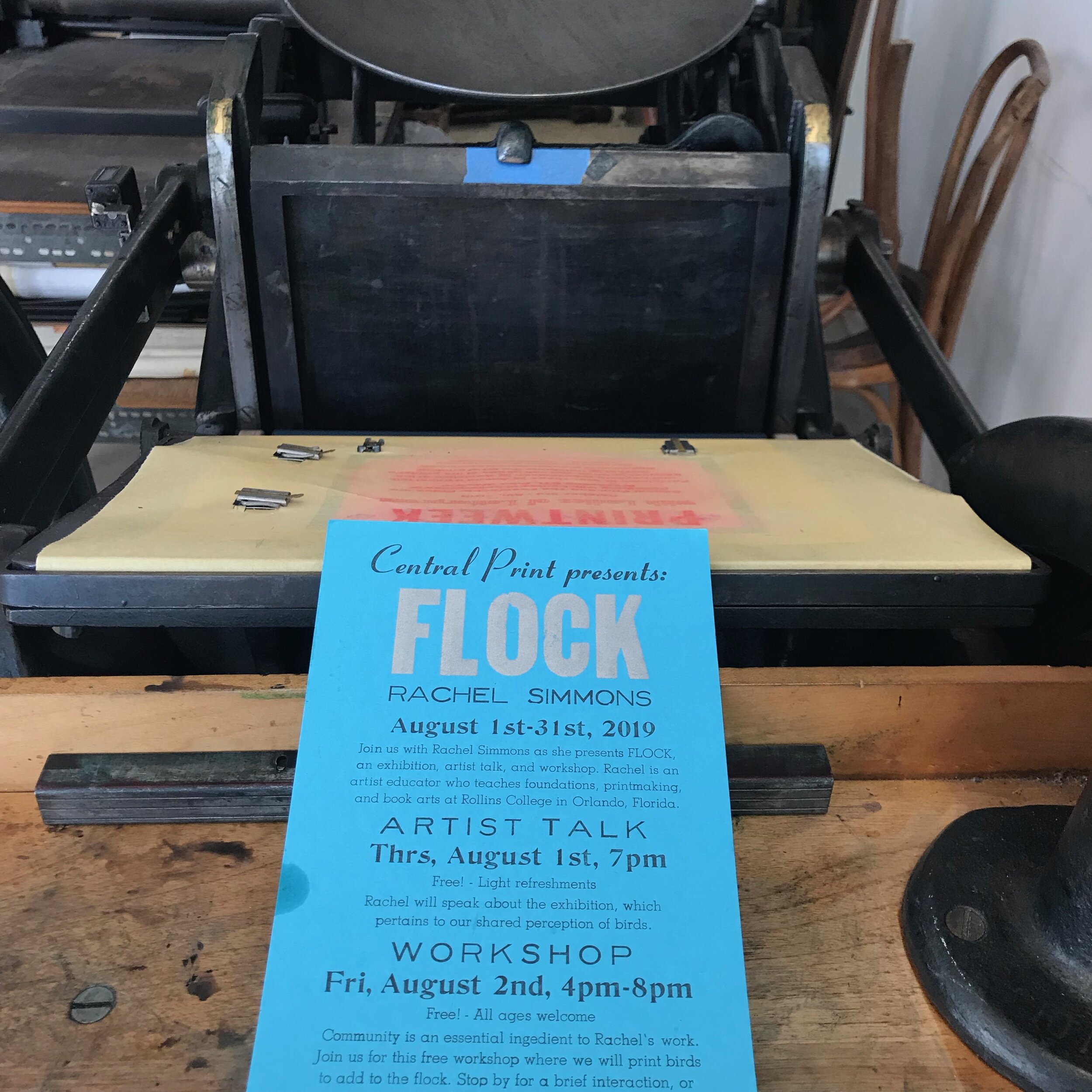

And that’s how Central Print fulfills its mission, by being an essential part of the fabric of the neighborhood. When I heard director Marie Oberkirsch speak at Hamilton Wayzgoose last year about Central Print’s mission to “to preserve the craft of letterpress printmaking, expand, and modernize its use while building awareness of St. Louis’ historical role in the development and growth of printing,” I knew right away that Central Print was doing something special and that I wanted to bring FLOCK there so I could be a part of it.

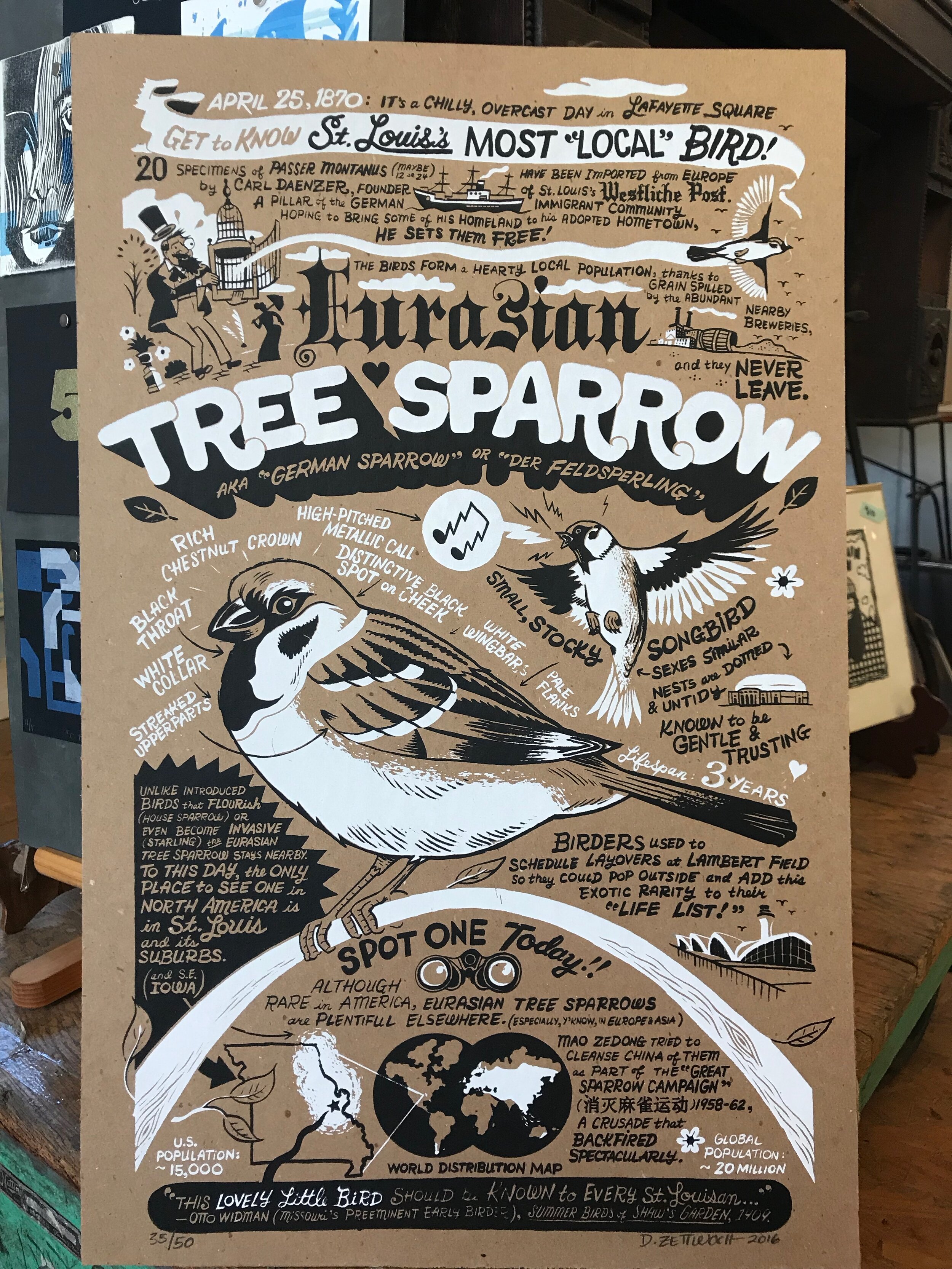

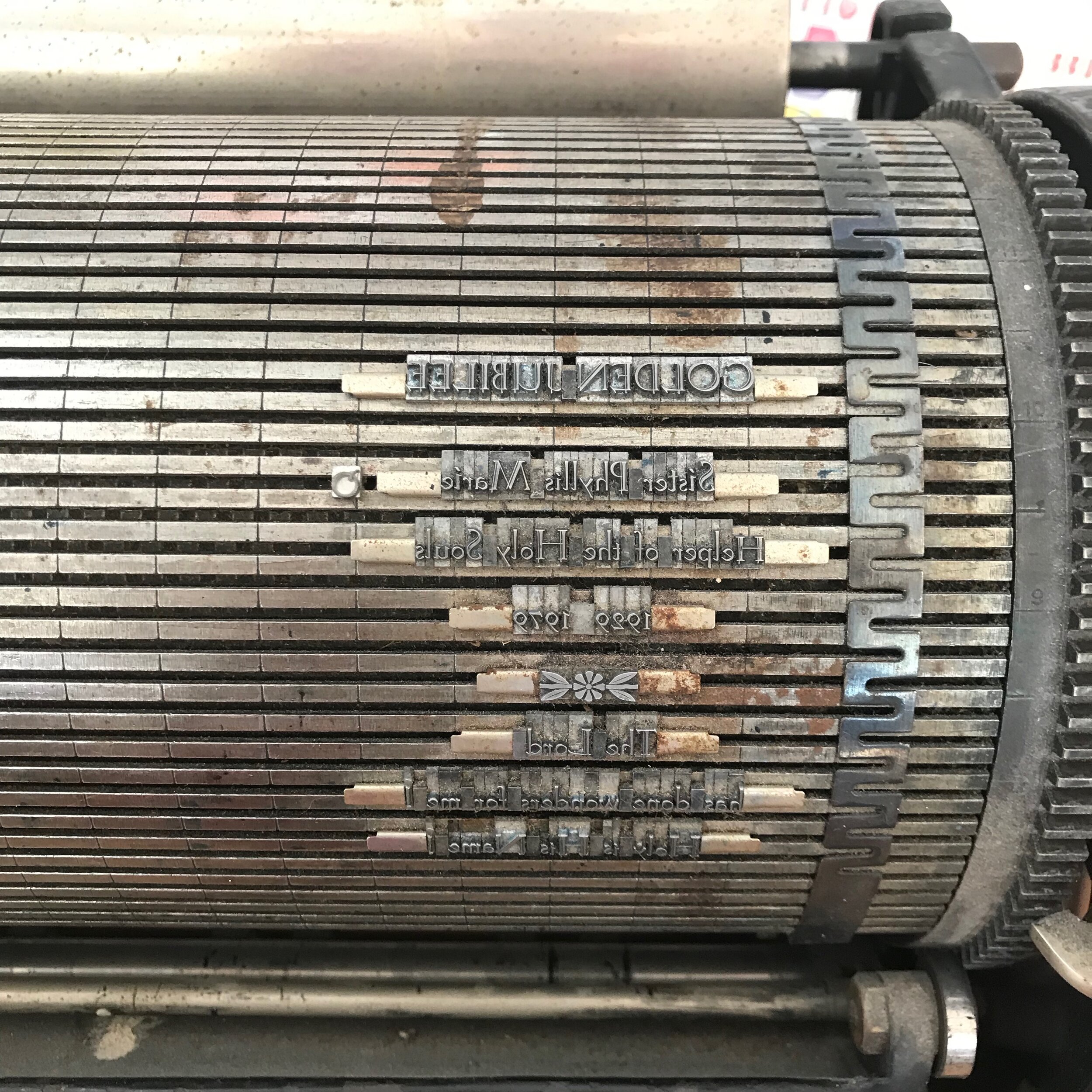

We started my visit on August 1st by installing the existing FLOCK prints on a long wall made of strips of reclaimed wood. The warmth of the wood wall added a new and exciting dimension to the work. Then I gave a slide talk about my practice, my travels and my current body of work The Language of Watching. Several of my artist’s books and collected field guides were on hand. Early the following morning in unusually cool weather, a resident of the neighborhood (hereafter known as the Master Gardener) and her two young daughters met us to go birdwatching. We were on the lookout for the Eurasian Tree Sparrow, a bird introduced by homesick European immigrants which can only be found in St. Louis, but instead we saw goldfinches, great egrets, house sparrows, great blue herons, cardinals, mourning doves and house finches. The community garden was particularly active as was a huge rookery of great herons and egrets in an adjacent neighborhood. We walked to the Master Gardener’s house and explored her incredible garden which occupied several previously empty lots where a row of red brick houses had been built over one hundred years earlier. The family had also constructed a garden shed from red, gray and white glazed bricks salvaged from a demolished neighborhood church. On the way there, we’d passed a wood working studio where local kids were building a boat which they would launch the next day. On the same block was a boarded up local print shop, likely established in the 1870’s, but abandoned after they family went out of business. We talked longingly about the treasures inside, presses and type of all kinds no doubt. Though the streets in Old North were potholed, stop signs went missing and sidewalks became overgrown, the residents’ connections to one another were the real treasures of the neighborhood.

The workshop was scheduled for four hours that afternoon into the evening, and participants came through in waves. Some were local school kids, others were graphic designers and college students along with older adults and families. It was exactly the sort of mix you’d hope to see in a collaborative community project because different perspectives make for richer collaborations. I set out pre-made bird silhouette relief plates and mixed a range of ink colors including a gold and black inspired by my sighting of the goldfinch that morning. Participants were encouraged to take a look at FLOCK before printing and then choose a bird plate to roll up. During the workshop, I ran the press, talked to participants about what they were making, and pulled a print or two myself. I answered questions about the project, but mainly we engaged in making prints and talking about birds. My birdwatching companions from the morning came to the workshop, giving us the change to chat again about the goldfinch and the enormous rookeries of egrets and herons down the road which had made the local news. All of the new prints were gradually added to the existing FLOCK. We had opportunities to talk about how previous participants had created their bird prints, and how the St. Louis part of FLOCK would be unique amongst them.

By the time the workshop had ended, I received two gifts: a sweet little zine about woodpeckers by artist Dan Zettwoch and some gorgeous wooden bird earrings from the Master Gardener. And these were just the objects I was given—I also took with me memories of Timothy’s enthusiasm for combining outrageous colors and patterns; Kirsten O’Loughlin’s steady hand as she helped him print & cut out his silhouettes; and Marie Oberkirch’s positive vibes and encouragement.

Though I have been practicing socially engaged art since I started teaching at Rollins in 2000, I’m evolving as an artist as I learn new ways to connect with communities outside of my own. In the last 5 years, I have been intentionally seeking out opportunities across the US that are mutually beneficial—finding spaces where my practice can grow through an exchange of meaningful, interactive art making experiences with communities. As I see it, the function of art goes beyond self-expression, it it about making connections with others and fostering awareness. The ongoing creation of FLOCK isn’t so much about the prints themselves or even about the birds, it’s about generating discussion amongst participants as we all reflect on our relationship with nature. Birds and printmaking are simply the conduits for this discussion. Being together in a space where one’s hands are occupied by rolling ink makes discussion flow in a way that is both casual and profound. It’s the very idea of making things together, print by print, or rebuilding a neighborhood brick by brick, that forms community and a sense of purpose beyond oneself. The process of making has always captivated my attention and motivated my work. The discoveries, the open-ended questions, the mistakes and the successes when something goes right—all of this is exciting to share with others. As we work, we chat:

“How did your print turn out?”

“Oh, that looks really cool, how did you do that?”

“What is your favorite bird?”

“Last week there was a hawk in our backyard!”

“I remember a bird I saw in India once…”

Of course, as the artist and also the facilitator of these collaborative experiences, I’ve learned through trial and error that I need to establish a certain amount of structure while remaining flexible and spontaneous to allow these moments to unfold organically. Teaching has taught me this skill over and over again, but translating it to my professional studio practice has taken some adjustments—after all, I am not teaching, I am creating a situation where I collaborate with strangers on my work. They are related, but different. This round of FLOCK was unique in that I felt so connected to the community in such a short period of time. I think that’s just the magic of Old North.